THE METAMORPHOSES OF CLOSENESS Gabriela Warzycka-Tutak 8 I 2016 – 31 I 2016 City Art Gallery in Łódź CURATOR Dominika Pawełczyk TEXT Diana Rönnberg

A body was given to me, what do with it, so unique and so much my own?

Osip Mandelsztam*

Seeing is metamorphosis, not a mechanism..

James Elkins, The Object Stares Back: On the nature of Seeing

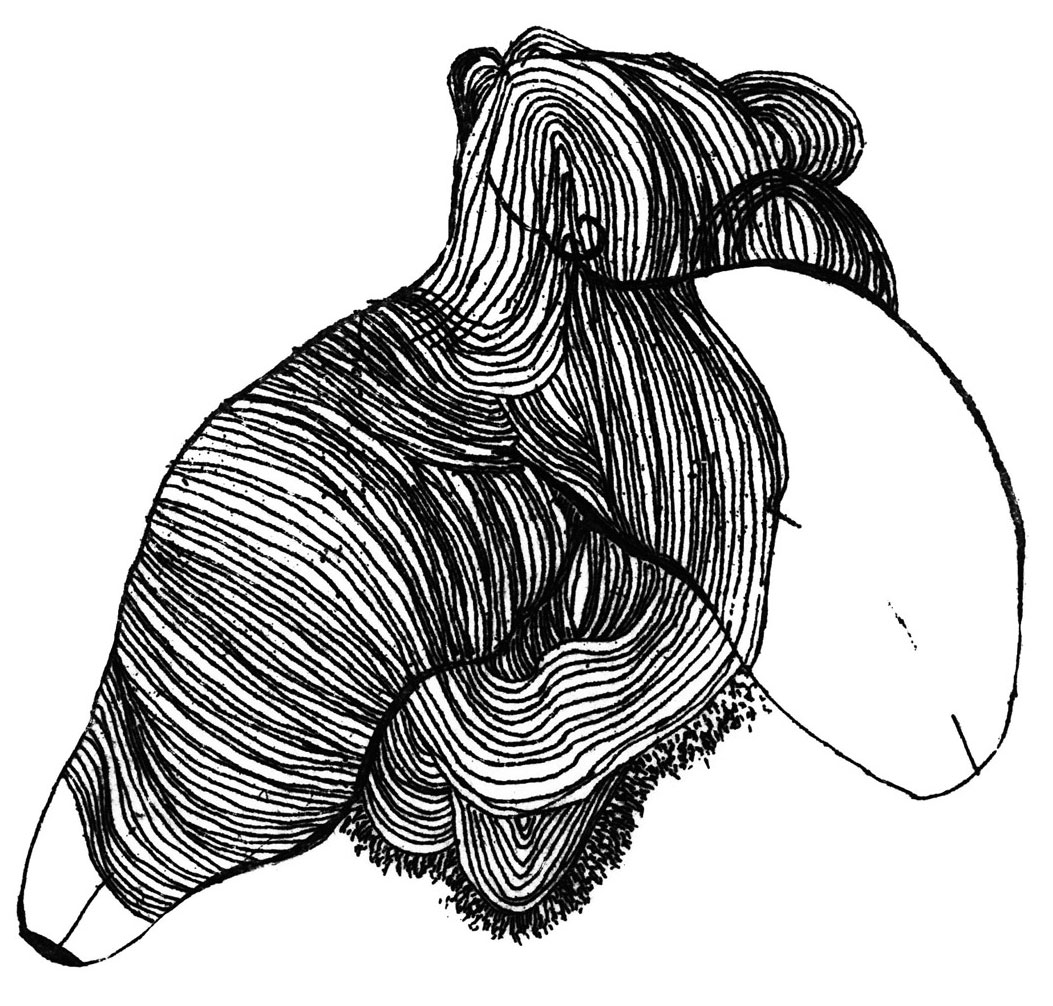

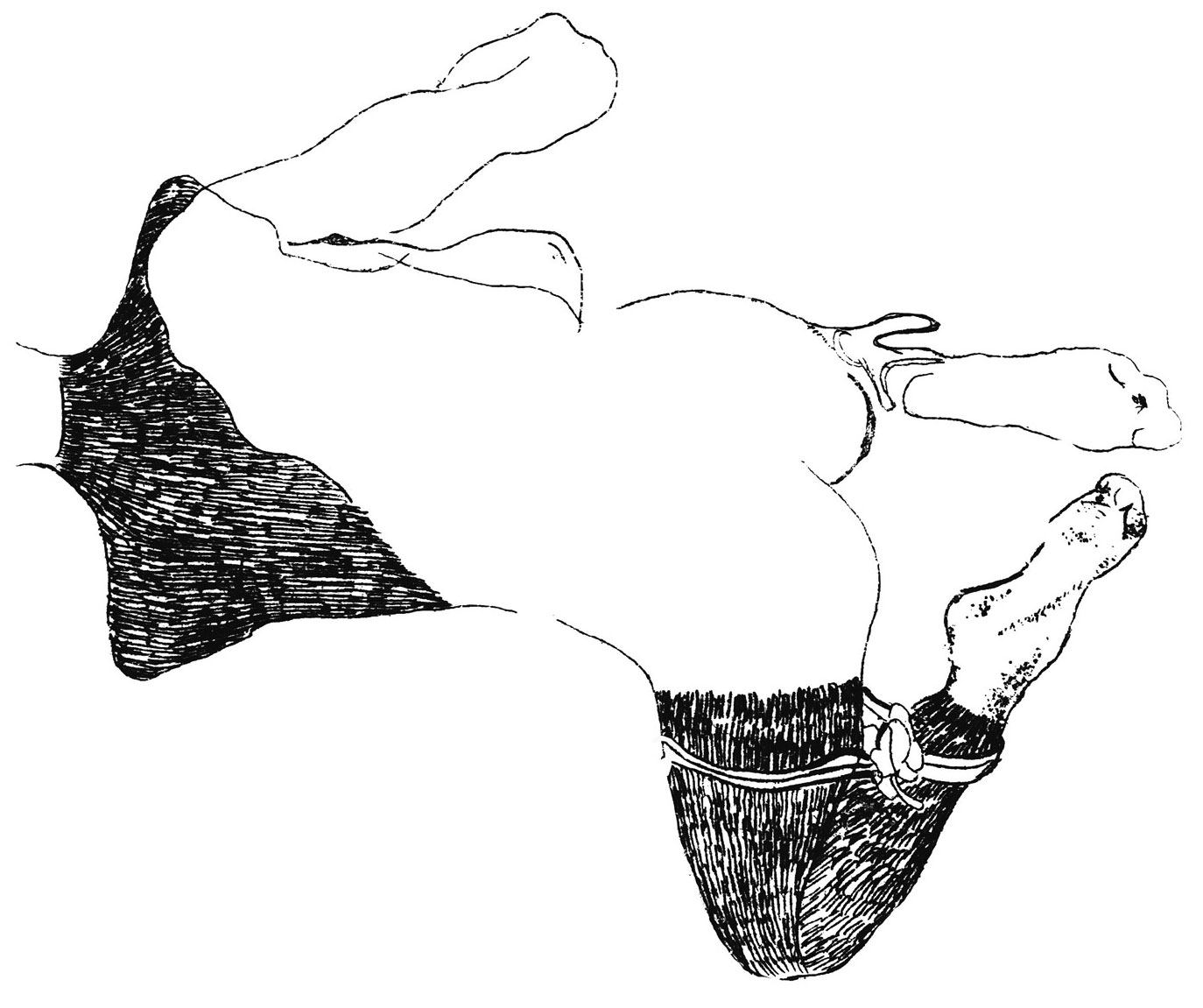

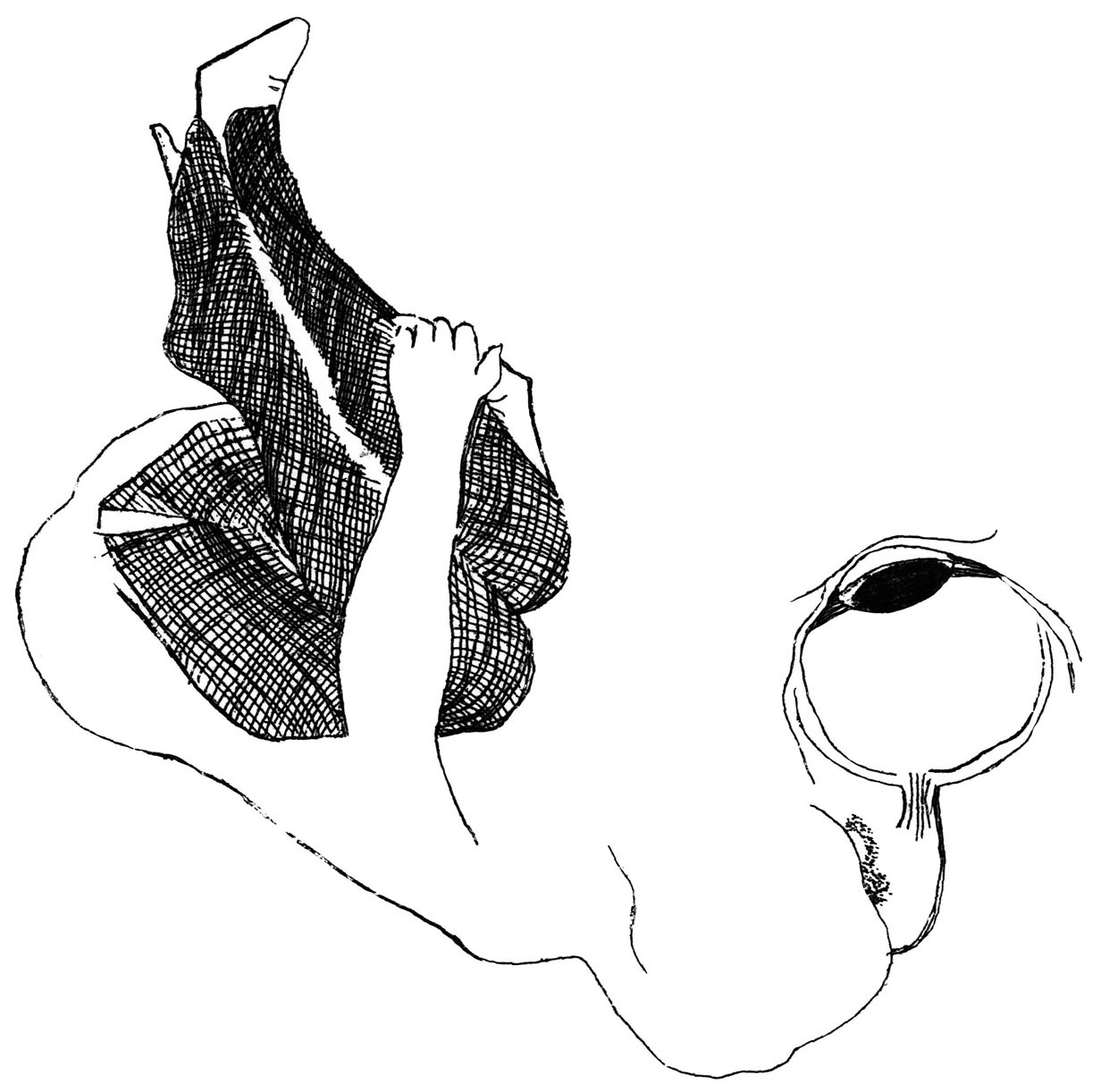

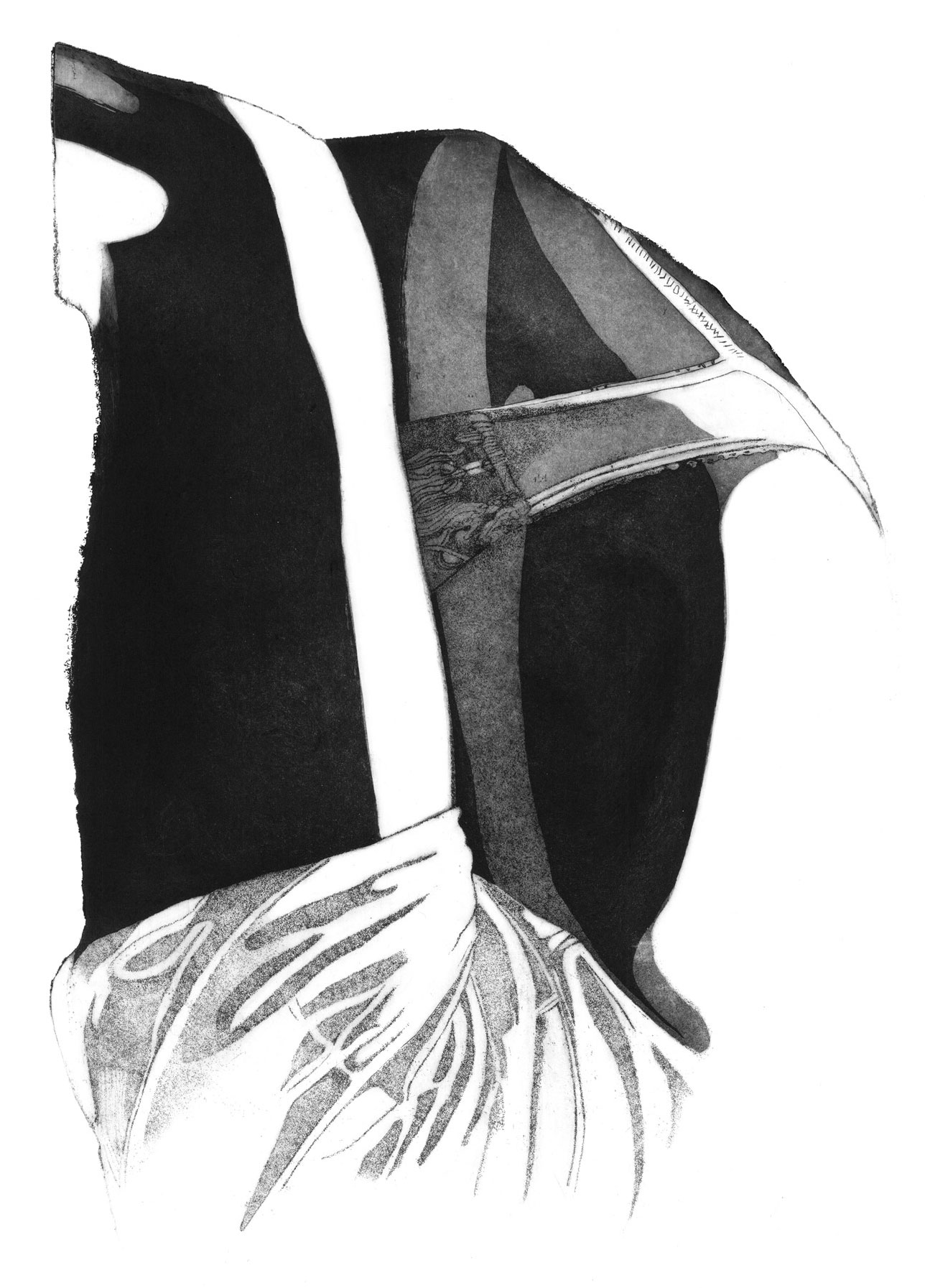

Gabriela Warzycka-Tutak uses lines to weave a story of a threshold, of an arbitrary border of the bodily in the process of constant transformation, of the senses that wither away in the bareness of the world.

In black, the artist traces outlines that refer to the darkest recesses of physiology. She portrays the vanity as well as the allure of stardust shaped into a dense mass over which we have been given control; full of landscape-like folds, majestic valleys and openings waiting to be filled.

Outlining and differentiating between endogenous and reactive states determines our entire being. As I look at Gabriela’s dismantled micro-construct in which frames and drawings, the whiteness from which lines emerge—they may even be lines of demarcation—co-exist with each other on different levels in a single space, it brings to my mind Jacques Derrida’s Parergon. The French philosopher, who strongly disputed the Kantian notion of universal beauty, centralised and fixed in unchanging frames, posed a question about what is beyond. A parergon comes against, beside, and in addition to the ergon, the work done (“fait”), the fact (“le fait”), the work, but it does not fall to one side, it touches and cooperates within the operation, from a certain outside. Neither simply outside nor simply inside**. Seen from this perspective, Gabriela is a surgeon and the tool she holds in her hand is a scalpel, she cuts off, excises, outlines, marks, makes us lose ourselves in the process. She dresses liquidity in robes.

In our conversation the artist uses the word destabilisation as a term that describes her current creative investigations. In a slightly paradoxical manner, the lack of stability becomes a departure point to construct a visual language that is extremely labour-intensive and requires precision.

Graphic printmaking is one of the basic and, at the same time, the least popular techniques nowadays, because the involved process is slow, it requires concentration and—indeed—a stable hand. Once a line is made on the metal sheet, there is no going back; the only thing one can do is to continue its course in a different direction in order to enhance its value.

At the same time, the majority of contemporary technologies largely offer the possibility of introducing corrections at nearly every point during the work. Gabriela gives proof of such an archaeological zeal not only in terms of the workshop. She unearths the subsequent layers of femininity entangled in a cultural game, deriving loose inspiration from such literary works as The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir from 1949 and Story of the Eye by Georges Bataille from 1928. Both these texts seem to whisper existentially from the afterworld: where does the ultimate border of imagination lie?

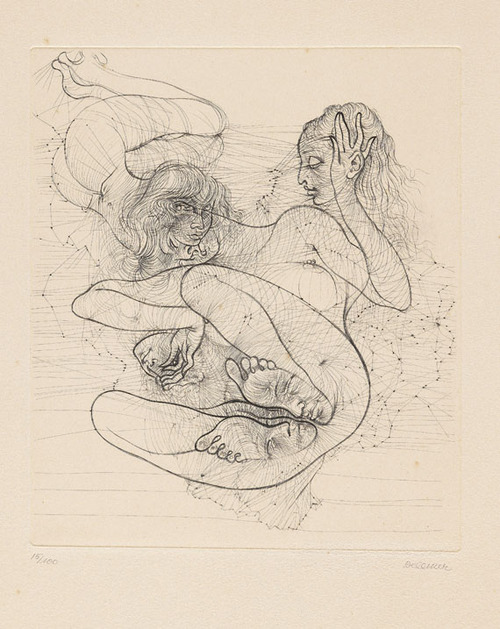

It is my impression that the works presented in the exhibition are characterised by strokes that bring to mind Surrealists, evoking the work of Hans Bellmer, an artist who gained renown mainly with pieces in which he confronted sexuality with the notion of innocence and decay. It is difficult to unambiguously state if this is an intended effect, Gabriela’s calculated strategy, or rather a profound influence of pre-war literature, which left an imprint on the aesthetics of the intuitive works. In any case, the viewer may get the impression of looking at paintings created at the time when Story of the Eye was written.

Hans Bellmer, illustration to Story of The Eye by Georges Bataille, 1947, etching

Once again we drift on the border; this time the border between the present and the past. What emerges from blackness is a labyrinth of anatomic configurations; condensed and at the same time pulsating with a breath. Gabriela confronts outlines of its two-dimensional walls with the display method, whose important aspect consists in a game with the space and the observer’s position.

The act of hiding some of the graphic prints behind a peephole offers an additional (safe?) distance. The frames suck the viewer’s gaze, thus highlighting not so much the illusory character of the very images, but above all the illusory nature of sexual intercourse itself.

The eye is a window and a symbol of vanitas, the eye hidden in the most intimate hollows of the body. The viewer’s eye that looks at the traces of their own transparency.

It was transparency that Susan Sontag demanded when concluding her essay Against Interpretation with a strong postulate: In place of a hermeneutics, we need an erotics of art***. Sontag encourages us to learn to see, hear and feel more, and interpret less in our encounters with art. Let us therefore transform into somatic transparency, into a threshold. Let us be inside and outside the blackness that holds the world together.

* Poem from 1909. Translated into English by Albert C. Todd and Max Hayward.

** Jacques Derrida, The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian Mc Leod (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), p. 54.

*** Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation, “Against Interpretation and Other Essays” (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1963), p. 37.